When disasters happen, the devastating effects often linger for years. As the years pass, one of the best outcomes can be to learn from the incident and take action to mitigate the lingering effects and work to prevent similar occurrences from happening again.

This week marks the 10th anniversary of the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster, the largest oil spill in U.S. history. Explosions on the oil drilling rig located off the coast of Louisiana killed 11 workers and caused nearly 200 million gallons of oil to be released into the Gulf of Mexico. Oil from the spill was dispersed into the gulf and onto the beaches and coastal areas, affecting some 1,300 miles of shoreline, hundreds of coastal communities, and tens of thousands of birds, fish, and other marine life. BP Oil claimed responsibility for the disaster and paid out more than $65 billion for claims and clean-up.

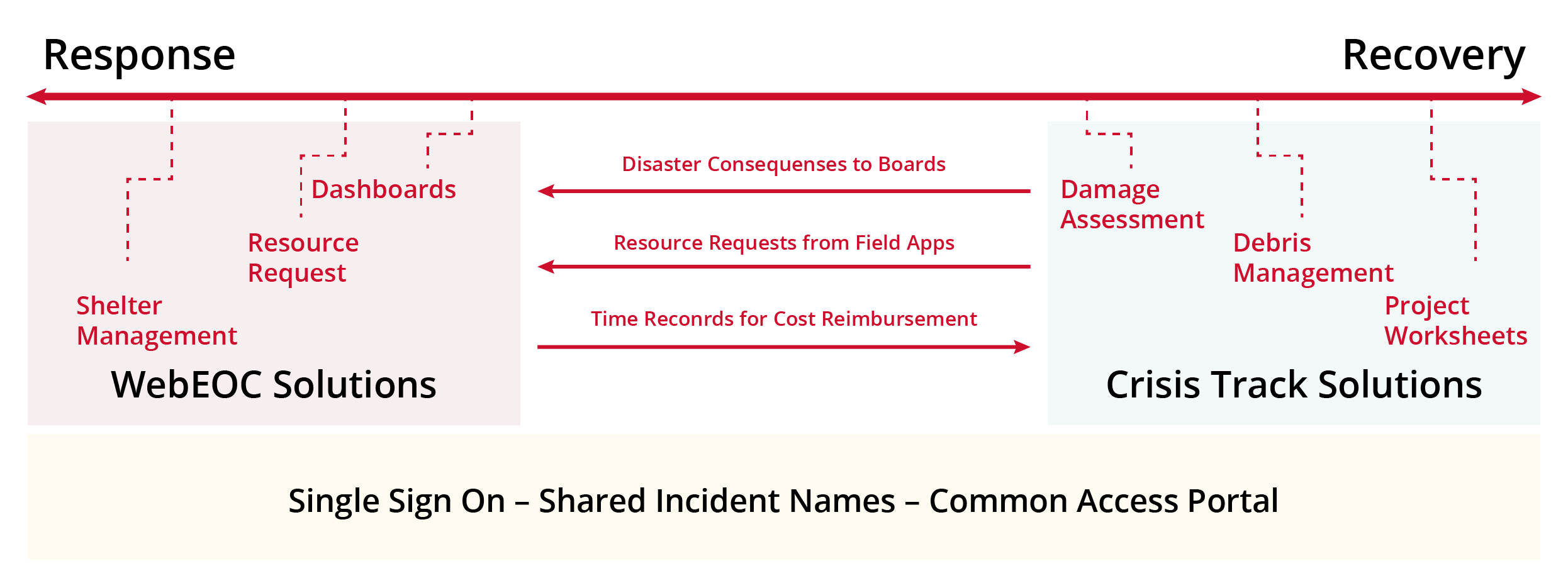

To respond to the disaster, nearly 2,400 vessels and 20,000 responders worked from multiple command posts to deploy more than 1.5 million feet of containment boom. This was all coordinated using Juvare WebEOC, which was provided by the state of Louisiana to BP and the U.S. Coast Guard in order to track the oil spill, maintain communications, and to connect all stakeholders throughout the incident and recovery. Over the course of the activation, the state issued WebEOC permissions to 846 new users, created 70 new positions unique to the oil spill (including 22 response positions), opened 8,574 missions, assigned 8,625 tasks, and logged 28,935 comments.

Lessons Learned

In light of this and other incidents in the oil and energy industry, many companies sought to find more effective solutions to comply with stricter regulations, to address health and safety risks, and to create more efficient and effective emergency processes, both during and after an incident.

Many energy companies adopted platforms like WebEOC, increasing situational awareness and the ability to make more informed, rapid decisions during an incident. WebEOC is also key for many to improving communication with emergency personnel, leadership, and employees, and creating a central source for consolidating critical information available to responders across multiple locations. This information includes maps of offices, offshore locations, hospitals, airports and other information needed quickly during an emergency.

A year after the Deepwater Horizon disaster, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) published a paper outlining many of the lessons learned during the incident response, and also worked with an interagency group to develop strategies for “enhancing the safety and health of responders to help managers, medical personnel, and health and safety representatives prepare thoroughly before an event and subsequently help ensure worker health and safety during and following an event.” Areas addressed included health screening, rostering, training, credentialing, exposure assessment and controls, medical monitoring, and medical surveillance.

Two years after the Deepwater Horizon incident, a new Disaster Response Center was opened in Mobile, Alabama to help federal, state, and local agencies with any future incidents in the Gulf of Mexico. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) the facility expanded readiness and response capabilities for disasters that could occur in the gulf area. Disasters like oil spills, fires, and other critical incidents including natural disasters like hurricanes and tornadoes, can occur at any time.

Ten years later, it seems emergency management agencies and the energy industry itself have taken great strides toward avoiding incidents like the Deepwater Horizon disaster. The key is to adopt a culture of preparedness, including detailed processes and technology to support response at a moment’s notice.

Click here to read more about how Juvare worked with agencies during the massive response to the Deepwater Horizon disaster.